Thought Leadership

ESG at the core of sustainable future food systems

ESG at the core of sustainable future food systems: A data-driven call to action

As global temperatures rise and food security becomes an increasingly urgent concern, the way we govern agricultural systems, especially those operated by smallholders in the Global South, demands urgent rethinking.

Small to medium-sized food systems generate half of the world’s food calories and support over 70 % of the global population 1. Despite their crucial role in food and income security, especially in regions like Sub-Saharan Africa, these systems, which are often driven by informal cooperatives, smallholder farmers, and community-led networks, face rising climate risks, inefficient energy use, and deep-rooted governance challenges, and are still underfunded and undervalued 2 3.

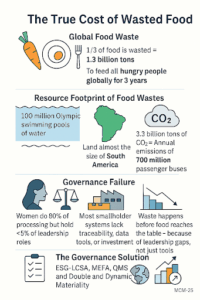

Additionally, nearly 30% of all food worldwide, around 1.3 billion tons annually, is lost or wasted, which could feed more than all the people who went hungry in 2023 for three years. This is not just a hunger issue; food wasted also uses about 250 km³ of water, enough to fill 100 million Olympic swimming pools, out of the 2,450 to 2,700 km² of blue water withdrawn for agriculture (See Figure above) 4,5. It consumes about 1.4 billion hectares of land—almost the size of South America (1.7 billion hectares). Food waste also results in about 3.3 billion tons of CO2 emissions, equivalent to driving 700 million passenger buses annually. It leads to the loss of roughly 30 exajoules of embedded energy each year, enough to power all households in Africa for six years, and causes $1 trillion in economic losses, which could be used to build 20 million small schools in Africa. When food is wasted, so too are all the resources that went into growing, processing, and transporting it 6.

Often overlooked is the fact that poor governance, rather than just technology, underpins many of these issues, particularly at the smallholder level. Who makes decisions? Who controls funds? Who leads? Who is more involved in staple food production? These questions are just as important as yields and efficiency. Without smarter, more inclusive leadership, even well-intentioned sustainability efforts can falter. It’s not only about advanced engineering tools but also about good and responsible governance.

The hidden ESG challenges in food processing

While corporate ESG strategies have traditionally focused on emissions or boardroom diversity, the governance of grassroots and staple food systems is sometimes where climate risks, gender inequity, and inefficiencies converge and where the most significant opportunities for sustainable transformation lie.

Across food systems, especially in low- and middle-income countries, processing stages are energy- and labour-intensive, highly informal, and governed by unstructured or exclusionary decision-making. In the case of cassava, for instance, the roasting stage alone accounted for 94% of energy use and 24% of global warming potential. Yet, similar high-emission bottlenecks exist across other staple crops, such as drying in rice systems or milling in maize production 3.

These hotspots are not just technical; they are governance failures. Decisions about equipment, revenue sharing, and sustainability adoption often occur in cooperatives or community systems where data is lacking and women, despite comprising most of the labour force, are excluded from leadership.

Why double and dynamic materiality matter

In response to this challenges and need to have credible data, our recent European and African Union partnership-funded (LEAP-RE) research, published in Sustainable Production and Consumption (Elsevier, 2025) applied a multi-framework approach combining Life Cycle Sustainability Assessment (LCSA) for evaluating Environmental, Economic, and Social performance, Material and Energy Flow Analysis (MEFA) to account for all resource (Materials, energy, human workforce etc.) inputs and outputs at every stage, Quality Management Systems (QMS) to ensure traceability and improve product consistency and Dynamic and Double Materiality (D&DM) assessments to simulate how systems respond to policy, climate, technology, market prices and investment changes ((examining both ESG impacts and ESG risks). The multiframework is automated using machine learning.

This approach was used on staple food processing systems, focusing on the cassava processing chain in West Africa. It showed that, like other critical staple food systems in the Global South, women make up 80% of the workforce but are mostly excluded from decision-making.

Rather than static metrics, our framework simulates how systems might evolve under different scenarios. For instance, in the cassava case, replacing wood fuel with a solar-biogas hybrid system reduced GHG emissions from 9.02 to 3.41 kgCO₂eq/kg of product. Profit margins increased from 34.4% to 52.5%.

This model can be applied to any value chain with available or estimable ESG data. It is scalable, adaptable, and aligned with investment goals—crucial for systems aiming to access green finance or carbon credits.

The governance blind spot: Gender and equity

In nearly all small to medium-scale staple food systems, women perform most of the labour but are seldom involved in governance. This creates a crucial gap: those who support these systems have limited or no say in decisions about technology, climate strategies, or financial incentives.

Governance reforms, including inclusive leadership, transparent profit sharing, and ESG reporting training, are crucial. Without these changes, well-intentioned sustainability efforts might inadvertently perpetuate inequality.

Why this matters for ESG boards and institutions

As ESG standards grow more complex—driven by regulations like the Corporate Sustainability Reporting Directive (CSRD) and IFRS S2—organisations and boards need to oversee beyond Tier 1 suppliers. Managing primary food systems will play a larger role in ESG results, reputation, and waste reduction efforts, ultimately aiding value creation essential for a fair and efficient energy transition toward SDG 2030 achievement.

Boards should:

- Ask more profound questions about where their supply chains begin.

- Promote data-driven governance tools that map ESG risk at the base of the pyramid.

- Integrate scenario-based ESG modelling into agricultural or any process value chain assessments.

- Encourage gender-equitable leadership and transparent reporting in cooperatives.

A call to action for governance leaders

To create sustainable systems, it’s essential to move beyond viewing production and processing issues as purely engineering and technical problems. Instead, these should be seen as governance priorities. Tools such as LCSA, double materiality, and AI-driven ESG modelling can be utilised across various sectors beyond agriculture to improve environmental outcomes, promote equity, and strengthen economic resilience. Achieving this requires courageous governance practices that empower local stakeholders, prioritise transparency, and welcome innovation.

As a renewable energy and ESG expert, I believe the future of ESG lies not in abstract frameworks, but in practical, inclusive, and data-driven governance — designed to optimise resource use and build resilience to climate change. This kind of governance must be embedded across systems and sectors, ensuring that sustainability is not just a goal, but an operational reality at every level.

References

1. Dhillon, R. & Moncur, Q. Small-Scale Farming: A Review of Challenges and Potential Opportunities Offered by Technological Advancements. Sustainability 2023, Vol. 15, Page 15478 15, 15478 (2023).

2. FAO, IFAD, UNICEF, WFP, WHO. In Brief to The State of Food Security and Nutrition in the World 2024 – Financing to end hunger, food insecurity and malnutrition in all its forms. Rome. The State of Food Security and Nutrition in the World 2024 (2024) doi:10.4060/CD1254EN.

3. Mwape, M. C. et al. Life cycle sustainability assessment of staple food processing: A double and dynamic materiality approach. Sustain Prod Consum 56, 343–363 (2025).

4. 11 facts about food loss and waste – and how it links to sustainable food systems | World Food Programme. https://www.wfp.org/stories/11-facts-about-food-loss-and-waste-and-how-it-links-sustainable-food-systems.

5. Mekonnen, M. M. & Hoekstra, A. Y. Sustainability of the blue water footprint of crops. Adv Water Resour 143, 103679 (2020).

6. Abiad, M. G. & Meho, L. I. Food loss and food waste research in the Arab world: a systematic review. Food Secur 10, 311–322 (2018).